A Journey Through History: Toward a Political Complexification

10 minutes read

The 6th century was a delicate period for Japanese history. By the beginning of the century the Yamato rulers successfully expanded their territorial control, extending their influence even across the sea, in the southern Korean regions. However, their predominance was short-lived as this kingdom established in the centre of Honshū Island was not able to withstand the consequences of its rapid ascension. Rulers failed to efficiently manage the vast territories under their influence, as seen previously, and were often forced to sedate rebellions on the southern borders of the realm. This situation was exacerbated after the failure of a military campaign in Korea in 531, which resulted in the loss of Yamato’s protectorate in the region, as well as a growing political instability within the management of the kingdom. A redefinition of internal socio-political structures was happening within the court as ruling households were gaining influence over the emperors’ affairs. Conflicts around the adoption of continental skills and philosophies were causing households to fight in order to secure the enactment of their preferred politics. This situation ultimately witnessed the emergence of a powerful clan, the Soga (Soga uji 蘇我氏), who used wedding politics to ensure their solid position in managing Yamato kingdom’s affairs, laying the basis of what will later be concretized as the first important administrative reform of Japan.

Sogatsuhiko jinja shrine, situated in Nara prefecture, is said to have a deep connection with the Soga clan.

© Wikimedia Commons, Saigen Jiro.

New Socio-Political Structures

The first historically attested form of kingship in Japan has been attributed to the realm of Emperor Ojin and the Naniwa court in the 4th century AC. Ojin and his dynasty ruled as O-kimi and Hi no miko, titles associated with the deities of the Sun, and relied on local subjects to effectively manage the Yamato territories. The emperor’s family had an important religious role, as they dictated and paced the seasonal activities of rice planting and harvesting.

Portrait of Emperor Ojin, from ‘Shūko Jisshu 集古十種’ published by ‘Kokusho Kankōkai 国書刊行会’

A century later, sometime around the 5th century, the imperial court was organized through the distribution of hereditary titles, kabane 姓, upon the representants of smaller social units called uji 氏, whose structure might have been similar to that of clans subordinated to the emperor’s rule. The apex of this system was embodied by the titles of Omi 臣 and Muraji 連.

The first was bestowed upon regional households that benefited from a certain independency from the imperial family, often defined by the area they originated from. Regarded as the noblest among their pairs, households defined by an Omi title were qualified to provide consorts to the emperors – a practice that has been regularly used by clans throughout Japanese history to affirm their power and influence over the political affairs. The first to systematically enact such strategies was the Soga uji.

Terracotta. Haniwa (funerary clay statue) of a chieftain with crown and sword. © The Trustees of the British Museum.

Terracotta. Haniwa (funerary clay statue) of a warrior.

© The Metropolitan Museum

On the other hand, the Muraji holders rarely married their daughters with the imperial family, a detail that has led many scholars to believe that these households might have been subordinates of the emperor and served him by their professions. Most representative households of the time were the Otomo and Monobe uji, who dwelt in military affairs, as well as the Imbe uji associated to religious activities. Worth of notice is a practice within the Muraji-type households, which consisted in claiming a descendance from deities appearing in the mythological episodes leading to the constitution of the Yamato kingdom. For some scholars, such episodes were straightforwardly crafted by these households, while others associate such practice to a strong desire of recognition within this political effervescence.

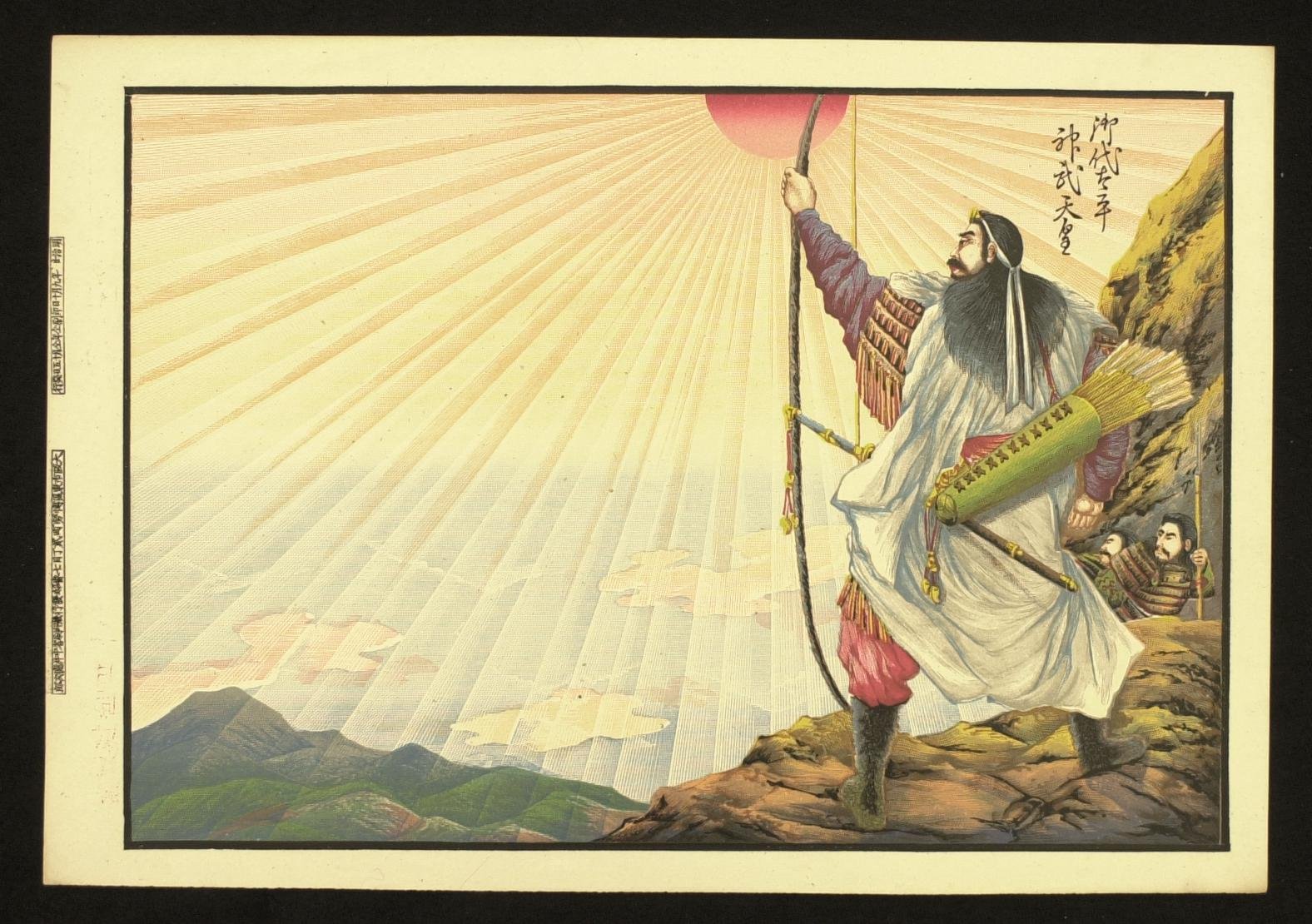

The descent of the heavenly Ninigi, mythical founder of the imperial dynasty, and the establishment of the Yamato kingdom by – the just as much mythical – emperor Jimmu have been the episodes more frequently quoted by the Muraji households to strengthen their claims.

Nakai Tokujiro (publisher). Advertisement (hikifuda), representing armed Emperor Jimmu in the sunlight, 1906.

© The Trustees of the British Museum.

All the Omi and Muraji households were represented and led respectively by an O-Omi (Great Omi) and an O-Muraji (Great Muraji), whose tasks were to effectively enact imperial policies, as well as help the emperor rule the land. In sum, there was some sort of mutual cooperation and control between the emperor and the representants of the ruling classes. This system proved to be effective in managing Yamato’s affairs until the middle of the 6th century, when the scarce incisiveness of emperor Keitai and his successor, emperor Kinmei, created a void that households were naturally compelled to fill, sparking a certain internal turmoil, which in turn was further aggravated by the Korean expedition’s failure.

Statue of Emperor Keitai, at Mt.Asuwa in Fukui prefecture. © Wikimedia Commons, 立花左近

Portrait of Emperor Kinmei, 1894, from the series 100 portraits of successive generations of emperors 御歴代百廿一天皇御尊影 published by San'ei-sha 三英舎.

Internal Quarries

The first creaking of the Yamato kingdom’s fragility was heard from a southern province situated in the Kyūshū island. In 527 the Iwai family, ruling over the Tsukushi region, opposed to the Yamato expedition in Korea and blocked the kingdom’s forces for well over a year. Such happening confronted the court with the reality of their difficulties in managing the growing power of long-established regional clans.

Amanoiwatoyama Kofun from the Yamekofungun group of burial mounds, in Fukuoka prefecture. These burial mounds have been identified as being the tombs of members of the Iwai family ruling over the Tsukushi region, in Northern Kyūshū.

©Wikimedia Commons, Saigen Jiro.

The Iwai rebellion rose awareness within the ruling class that strong families could become a vital threat to Yamato if not dealt with correctly. The closer to potential enemies such as the Korean kingdom of Silla, the higher the danger of letting such potencies grow rogue. An administrative reform to restore some power balance in the archipelago was long due since important families were prospering. One of the precursors of such important planning was the instauration of specific lands managed directly by the ruling kings of Yamato and their offspring. Acting as some sort of royal estates established across the archipelago, such territories helped manage the political affairs, having a better influence over the local population and important families. With time these regional possessions have proven to be important assets for their holders, strengthening their military and political positions as well as becoming sources of income.

In concomitance with this new organization of the kingdom, the death of emperor Keitai in 531 led to a ferocious dispute over the designation of his successors, fuelled by the recent military debacle in Korea. Strong and influential clans competed to enthrone their designated heir and an openly debated political clash soon manifested itself. The main competitors to the heir course were the Otomo, a Muraji-type uji in charge of the military affairs, and the Soga, an Omi-type uji focused ion administering internal affairs. This confrontation was centred around a possible retaliation in Korea, a resolution that the Soga uji opposed firmly as too demanding in resources. The clan leader, Soga no Iname, perceived how Yamato was weakened by the recent defeat and sought after a better consolidation of the kingdom rule over the archipelago. History tells us that the Soga uji managed to secure their choice over the Yamato throne, emperor Kinmei, marrying to him two women of the clan in the process. The Soga clan was thus set up to become the first of many influential clans that made marital politics into the roots of their ascension.

Empress Suiko, daughter of emperor Kinmei and Soga no Kitashime – daughter of Soga no Iname – ruled from 593 until her death in 628. The Japanese book ‘The Prince Shotoku exhibition (聖徳太子展)’, NHK (NHK promotion), 2001.

Emperor Yōmei, son of emperor Kinmei and Soga no Kitashime – daughter of Soga no Iname – ruled from 585 until his death in 587.

However, such monopolisation of power did not go unnoticed as several clans began opposing the growing Soga hegemony over the following century. Yamato soils were periodically stained by the blood of the land’s inhabitants and leaders who dared openly oppose the Soga ascension. Ironically enough, this period has been recognized as a crucial moment in Japanese history. The Soga clan actively promoted the adoption of knowledge and techniques brought to the archipelago by continental migrants, while advocating for foreign philosophies such as Confucianism and Buddhism. This positioning close to foreign matters was ill-received by the more conservative clans that constructed their identities around autochthonous weltanschauung, which provided the core of what would be described later as Shinto. Unfortunately, since our time here is limited, we will focus the next article entirely on the parabola that was the rise and fall of the Soga clan, as well as their consequences for the political balance of the Yamato kingdom.

Written by Marty Borsotti