People from the Japanese Lore: The Soga Clan

Our journey through history is slowly heading toward a period called ‘Asuka enlightment’, a pivotal moment in Japanese history, when the sinicization of Yamato court’s elites laid the foundation of what would eventually become the Japanese nation. However, before tackling this rich period, a detour is due to present the Soga clan, which can be considered, to a certain extent, as the promotor of this complex cultural revolution.

This topic is particularly delicate due to the lack of diversification in sources related to the rise and decline of this important family. The origins of the clan are deeply connected with the mythological tales of the archipelago, narrated in the Nihon Shoki and Kojiki, which are not reliable historical sources. Its decline, on the other hand, has been recorded solely by sources that display a clear sentiment of opposition in their regards, since the fall of the clan was orchestrated to prevent their supremacy over the court. Therefore, what is presented below stems from what we currently know about this period; even when we try as much as possible to deliver a neutral recite, further research on the topic may contradict this article.

Sogatsuhiko shrine, situated in Nara Prefecture, is often indicated as the place where the tutelary kami of the Soga clan have been enshrined. © Saigen Jiro, Wikimedia

The Roots of Soga’s Supremacy

The Soga emerged as a powerful clan during the 6th century. Their ascension was a direct consequence of the political complexification happening within the Yamato kingdom elite. Contrary to many clans who focused on their military or religious services, the Soga family prioritized mastering continental knowledge and techniques acquired through commercial and diplomatic exchange. The clan soon became the main patron for continental migrants, building an intellectual elite through which they were able to learn the Chinese administration system. With the support of these valuable resources, the Soga became important and trustworthy counsellors in the management of Yamato kingdom’s affairs. Unfortunately, due to their connections with the continent, more traditionalist clans perceived them as a potential threat. These tensions grew especially when the Soga leaders began to publicly endorse the adoption of Buddhism, a foreign doctrine perceived by their opponents as incompatible with the indigenous belief. Several internal conflicts burst out, motivated, at least on the surface, by religious reasons, but translated in practice as attempts to reduce the Soga influence over the court. However, on many occasions the clan was able to best its opponents and further strengthen its political position.

Shitennoji in Osaka prefecture, regarded by many as the oldest japanese Buddhist temple, originally built under the direction of Shotoku Taishi in 593 AC. © 663highland, Wikimedia Commons

A Mythical Founder and His Historical Offspring

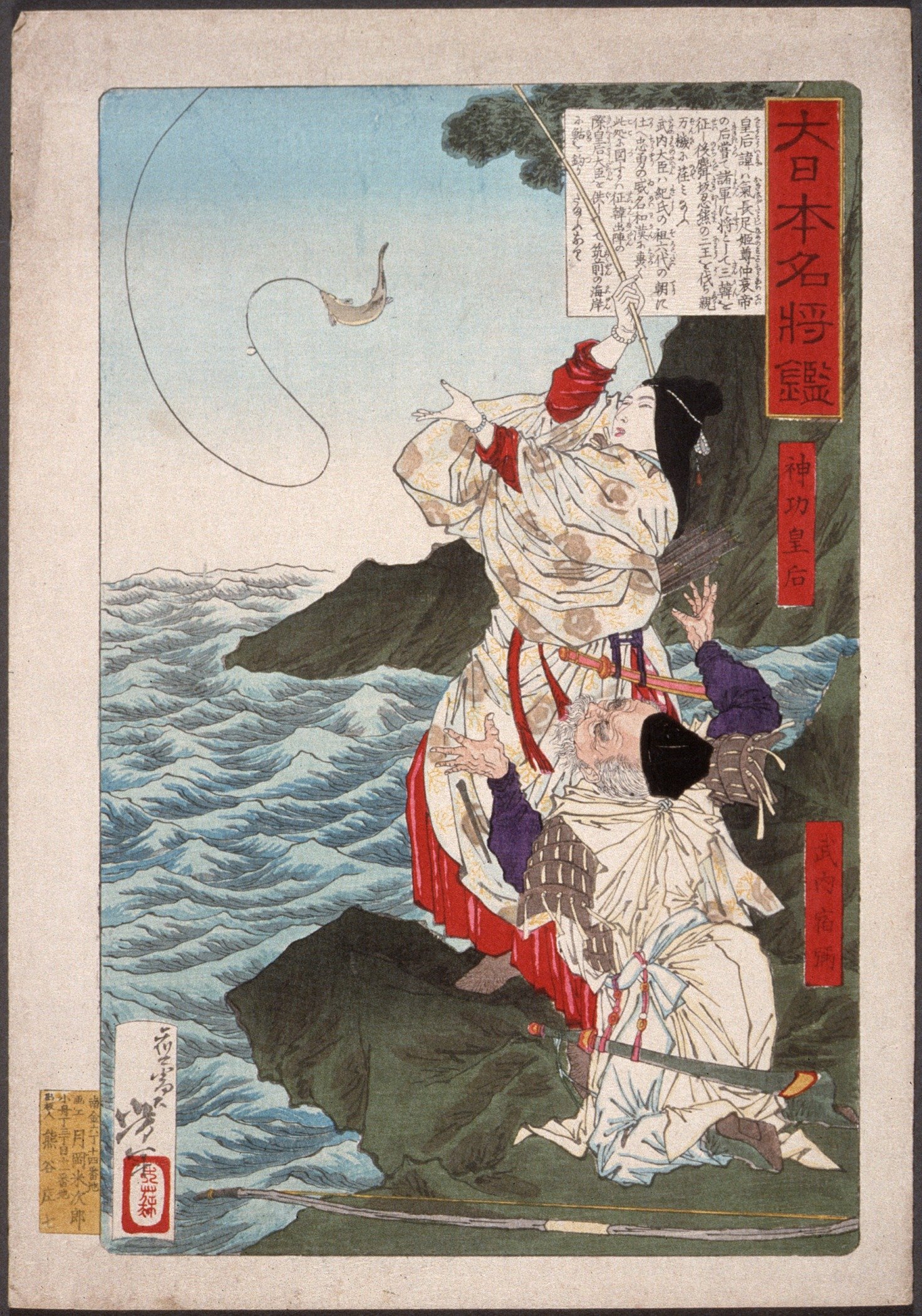

Tsukioka Yoshitoshi (1839–1892) Empress Jingū and Takenouchi no Sukune from the series ‘Mirror of Famous Generals of Great Japan’ (Dai nihon meishō kagami 大日本名将鑑). © Los Angeles County Museum of Arts

The Soga clan has been often associated with a mythical figure deeply involved within the Korean expedition led by Empress Jingū in the 3rd century AC: Ishikawa Sukune. His appearances are often related to foreigner matters, such as expeditions to the northern borders of the Yamato rule, as well as the already mentioned Korean expedition. It is said that among his many feats, this mythical figure single-handedly subdued the Korean kingdom of Silla and subsequently became the first holder of the title of Ō-Omi (大臣), head of the Omi clans. Moreover, Sukune has often been portrayed as a loyal and trustworthy minister of the Yamato kingdom. Thus, it does not come as a surprise that the Soga leaders, who based their fortune on their relations with the continent, tied their genealogy with this figure to legitimize their own position of Ō-Omi. Having an ancestor involved in continental matters and recognized as trustworthy might have improved Soga’s position, especially when seeking approval of their political opponents.

The link that ties the Soga genealogy to its mythical ancestor lays within the figure of Soga no Machi, who lived during the 5th century and was said to be the grandson of Ishikawa Sukune. Soga no Machi initiated the rising process of its clan by gaining important positions within the court of Emperor Yuryaku (418–479) while already developing tight relations with continental migrants.

The Wedding Politics of Soga no Iname

Soga no Iname (506–570), grandson of Soga no Machi, has been predominantly remembered for being the first to publicly endorse the adoption of Buddhism as an Ō-Omi, provoking a strong reaction from the more conservative clans. This friction over the adoption of a foreign belief led to several conflicts, in which the Soga were opposed by the Monobe and Ōtomo clans, representants of the Muraji-type clans and more traditionalist by nature. However, we should consider that behind this ideological confrontation was a deeper struggle for the political predominance over the Yamato kingdom. In many regards, the opposition to Buddhism was, in reality, an opposition towards the Soga predominance, and not the contrary.

It is said that Iname’s endorsement to Buddhism was such that he arranged his own residence as a temple to enshrine a Buddhist statue imported from the continent. This act was perceived as an open defiance towards the local deities and led to the Monobe clan’s retaliation, who burned the temple and threw the statues into the Naniwa harbour. Nonetheless, despite this fierce opposition, Soga no Iname managed to plant the seed of the subsequent predominance of his clan by marring two of his daughters into the imperial family. These wedding politics proved to be a trump card in the hands of Iname’s successor, Soga no Umako, who was able to assure, through political schemes, the enthronement of his relatives, later known as Emperor Yōmei (540–587), Emperor Sushun (523–592) and Empress Suiko (554–628).

Soga no Umako, the Greatest Soga Leader

Soga no Umako inherited a relatively delicate situation from his father, mainly due to Iname’s religious positions. In fact, Umako became the clan leader during the rule of Emperor Bidatsu, who actively operated against the expansion of Buddhism, endangering by the same process Soga’s position. A major development in Umako’s quest for predominance was the death of Bidatsu’s spouse, Hirohime, in 575, and the emperor’s choice to make a Soga woman his new consort. The new empress most likely defended her clan situation during the last years of Bidatsu’s reign.

King Yōmei

However, the pivotal moment in Soga’s ascension happened within the power void generated by the sudden death of Emperor Bidatsu in 585, which led to a fierce conflict over establishing his successor. Mononobe no Moriya, supporting prince Oshisaka, the son of Bidatsu’s first spouse, was opposed to Soga no Umako, whose faith was placed in prince Anahobe, son of Bidatsu’s second spouse, daughter of Soga no Iname. History tells us that the Soga clan bested their rivals and enthroned their pick as king Yōmei, who was closely assisted by his uncle. Umako then continued his father’s wedding politics by marring another of his sisters to emperor Yōmei. The new empress bore four sons, among which was prince Shotoku Taishi (574–622), who will be presented in a separate article in due time.

It is not a mistake to affirm that by the end of the 6th century the Soga clan held a tight control over the Yamato kingdom, which was continually reaffirmed by Umako’s wedding politics coupled with his court intrigues. The death of emperor Yōmei in 587, only two years after his enthronement, did not undermine Umako’s schemes, as once again he was able to best the opposition led by the Mononobe and enthrone another of his nephews, Sushun, in 588. Umako’s quest for predominancy did not spare his kinship, which people of the time were able to witness not long after Sushun’s enthronement. According to the sources of the period, rumours saying that Emperor Sushun was planning to put an end to his uncle were circulating in the court. It is said that this climate of conspiracy pushed Umako towards a preventive strike, planning the assassination of Sushun. History tells us that Emperor Sushun died in 592 and was succeeded by his half-sister and aunt, Empress Suiko. Such development proved to everyone that Soga no Umako was now the effective ruler of the country, operating through the proxy of his enthroned relatives.

Tosa Mitsuyoshi (1539–1613) Portrait of the Empress Suiko, Eifuku-ji, Osaka prefecture.

The Soga Hegemony

It is not in our competence to judge Soga no Umako’s doings through a moral perspective, although it is quite certain that his schemes brought a certain unbalance to the political relations of the Yamato court. During Suiko’s regency, the Soga clan kept strengthening its power and influence over the management of the state’s affairs, exacerbating in the process their opponents’ dissatisfaction. Such predominance, and a certain degree of boldness, ultimately caused the fall of the Soga clan during the 7th century, as we will see during the continuation of our journey through history. During the following centuries, the Soga have been frequently represented as a greedy and cunning clan who disrupted the balance of the country and proved to be an unworthy family. Almost all the chronicles of the times display a certain anti-Soga attitude, often downplaying their action or straight-forward criticizing them as a potential danger that was fortunately avoided thanks to their demise. However, it must be noted, once more, that Soga’s adoption of continental practices and beliefs is probably what laid the cultural foundation to the ‘Asuka enlightenment’ and subsequent periods. Mastering the Chinese administration system and techniques, as well as its writing, enabled the Yamato court to conduct Taika reforms of 645, which revolutionized the state’s affairs management and were used, to a certain degree, until the end of the Edo period (1608–1868). By the same process, the first written chronicles of Japanese history, the Kojiki (712) and Nihon Shoki (720), were compiled and used by the Yamato sovereigns to portray themselves as equals in status to the Chinese emperors, a topic which we will further develop in our future articles.

Ishibutai Kofun, considered by many the tomb of Soga no Umako, Nara Prefecture.

© 663highland, Wikimedia Commons

Written by Marty Borsotti